To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories.

On February 22, a fire swept through a 14-story apartment block in the Campanar neighborhood of Valencia, Spain. Ten people died in the blaze. Smartphone footage showed an awning on a seventh-floor balcony catching fire at around 5:30 pm CET, before the flames rushed upwards. Within 15 minutes, the entire building was engulfed, aided by 40-mph winds. Suspended Ceiling Aluminum Panels

The inferno quickly drew comparisons to London’s Grenfell Tower fire, which killed 72 people in 2017. While what drove the blaze in Valencia is unclear, attention immediately turned to the building’s cladding—material added to the outside of high-rise blocks to improve insulation and aesthetics, and which helped the Grenfell fire spread so quickly. Until 2019, Spain, like many nations, permitted flammable materials to be included in cladding on new high-rises. While the law has changed, hundreds if not thousands of existing Spanish buildings are likely encased in non-flame-retardant panels.

The same danger lurks internationally. Many countries still allow highly flammable cladding to be used in construction. Others, despite banning dangerous materials on new buildings, still have older ones encased in layers of materials highly vulnerable to fire. “Valencia will not be the last one,” says Guillermo Rein, professor of fire science at the Department of Mechanical Engineering of Imperial College London. “Not in Spain, nor anywhere else.”

The world’s cladding crisis stems from another. In the 1970s, the oil crisis created a problem for architecture to solve: how to design more energy-efficient buildings in the face of soaring fuel prices. Facades were to be redrawn from the ground up. “They were once only made of stone, brick, or concrete and very simple,” says Rein. “But they play a complex role: the interface between inside and outside, sunlight and darkness, warmth and cold, noise and quiet.”

Integral to the design of new facades were synthetic polymers: materials made of chains of repeating subunits, and which are the main ingredient of household plastics. Versatile, lightweight, strong, and inexpensive, polymers became architects’ wonder material, offering improved insulation and faster construction time than concrete mixed on-site. It solved all their biggest problems, says Rein, except one. “All polymers are flammable.”

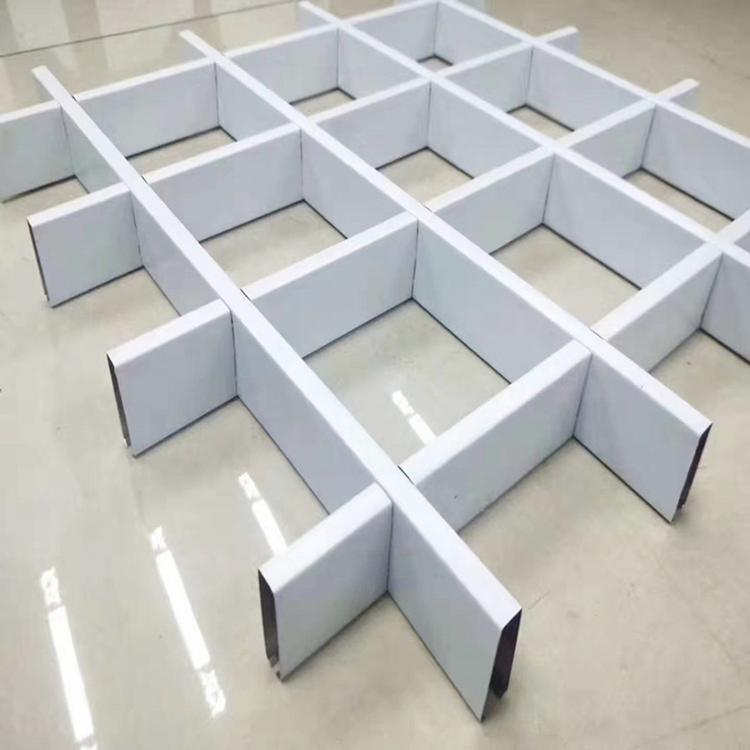

For more than five decades, a polymer core has typically been sandwiched between ultra-thin panels made from aluminum composite material (ACM) on the facade of modern high-rises. “Architects love what you can do with aluminum. You can curve the facade, add a shine, and make it visually appealing,” says Rein. “And it hides the ugly insulation beneath it.”

While commercial ACM manufacturers have always fire-tested these materials, before Grenfell, results would often be obfuscated from the building sector, says Rein. A typical test would see a blowtorch applied to the front of the ACM—the metal would sustain the flame long enough for the manufacturer to claim it was “fire resistant.” However, flammability comes from the polymer, not aluminum. And these tests didn’t necessarily engulf the material the way an actual fire would.

“If you turn the ACM 90 degrees, and attack the edge with the polymer exposed, the aluminum peels off in 20 seconds and a ball of fire rips, creating black smoke and big flames,” Rein says.

Crucially, it’s not just material itself that’s flammable—some features of modern architecture can intensify fire spread. The Valencia tower block, completed in 2009, had a ventilated facade, meaning it included an air cavity for improved insulation. But that also created the potential for the “chimney effect,” which also occurred at Grenfell: flames rapidly funnel upwards. “It’s an arsonist’s dream,” says Rein. “The fire goes inside, you cannot get it out.”

Before the Grenfell Tower Inquiry in the UK, which culminated in November 2022, Rein says fire safety engineers weren’t typically consulted during a facade’s design and construction. Instead, combustible components would often be signed off by independent assessors, extrapolating results from spreadsheet data rather than on-site testing—creating what were notoriously known as “desktop studies.”

While matters have tightened up in the UK, many countries still have loose fire safety regulations, says Rein—and high-rise facade fires have not only grown exponentially, but internationally. For example, there has been a spate of blazes in China and the United Arab Emirates—two countries known for recent waves of glittering, futuristic architecture. The UAE now has 18 recorded high-rise facade fires in just 13 years—swift evacuations and indoor sprinklers help explain why there have miraculously been no deaths directly attributed to the flames.

Douglas Evans, a Las Vegas–based fire protection engineer, says the problem is global—one of the deadliest facade blazes was a 28-story high-rise apartment block in Shanghai in 2010 that had polyurethane foam insulation. “Ten years before Grenfell, these sorts of fires began to pop up all over the world.”

The likes of Germany and the US have much more stringent regulations—the flammable cladding used in Grenfell was already banned in both countries. The US follows the International Building Code, which requires cladding for buildings taller than 40 feet to pass a rigorous test developed by the nonprofit National Fire Protection Association: the NFPA 285. Issued in 1998 as a response to the growing prevalence of flammable materials, its criteria include that vertical flames spread less than 10 feet (3 meters) above the window opening in the test, and that lateral flames spread less than 5 feet (1.5 meters) from the centerline of the window opening.

This means cladding within US high-rise buildings typically contains ACM with a higher flame-retardancy rating. “But there are allegations of high-rise buildings in the US that have been constructed of non-fire-retardant metal composite material,” says Maryland-based fire safety consultant William Koffel.

Guidance can only go so far: There is no unilateral body enforcing NFPA codes. Furthermore, US jurisdictions—including Washington, DC; Minnesota; Indiana; and Massachusetts—have pushed back and permitted the use of some cladding containing components that fail NFPA testing.

“Codes, standards, and testing are big cogs of the fire and life safety ecosystem we’ve devised,” says Robin Zevotek, an NFPA technical services engineer. “But there’s not one entity in the US, UK, Spain, or elsewhere with sole authority on enforcing the code at every level of the construction process. Without building owners investing in safety, willing to spend money, the system can quickly fall apart.”

Awareness of flammable cladding is one thing—getting rid of it is another.

In the UK, the cladding crisis rumbles into its seventh year. In the immediate aftermath of Grenfell, ACM panels started to be removed from high-rises across the country, and in the following years, the rules tightened on what materials could be used in construction.

But by 2020, more than half a million people were still estimated to live in homes with dangerous cladding across England. In many cases, apartment owners have been trapped in unsellable homes—mortgage providers are unwilling to lend to buyers for properties without certification that their external walls are safe.

While the government announced a £3.5 billion ($4.4 billion) cladding replacement fund for blocks over 18 meters in February 2021—and followed this with a Cladding Safety Scheme in July 2023 for buildings taller than 11 meters—as of January 2024, only 21 percent of unsafe buildings had been completely remediated, according to the government’s housing department. Fixing buildings has been slower and more expensive than expected, and there has been confusion over what the funding covers. As of October 2023, three-quarters of funding applications hadn’t resulted in money being dispensed.

This Kafkaesque situation risks other countries not wishing to remove flammable cladding, says Rein. If you reveal the extent of flammable cladding without a functional system for removing it, you risk collapsing the national real estate system, he argues.

Beyond bureaucracy, progress has also been hampered by the logistical challenge of replacing external materials on structures upwards of 50 meters high, says Zevotek. “The taller the building, the more likely it is to exceed the capability of scaffolding and ground ladders. Where once you could add facade material during construction, there’s no easy way to add new materials on a high-rise already up.”

In an industry traditionally hard-pressed against time and budgets, safety comes at a price. ACM cladding with a non-combustible core costs more than the flammable material previously wrapped around modern UK high-rises. “Safer solutions are rarely cheaper,” says Rein. “There was no mystery in how to make ACM much less flammable—the material is now being used in remedial works.”

With countless high-rises built with flammable cladding around the world, the next facade blaze is an inevitability, says Rein. The goal, therefore, should be fire prevention, detection, and suppression. “Extra layers of safety—sprinklers, good smoke detectors, better fire evacuation routes—can save lives,” he says.

The irony, says Rein, is that when fire safety is effective, no one knows it’s working. “The first item cut is never color, shape, or space—it’s safety. It’s only when it fails that you realize it’s missing.”

Updated 3-5-2024 11:20 am GMT: Douglas Evans’ name was corrected.

Don’t think breakdancing is an Olympic sport? The world champ agrees (kinda)

How researchers cracked an 11-year-old password to a $3M crypto wallet

The uncanny rise of the world’s first AI beauty pageant

Give your back a break: Here are the best office chairs we’ve tested

Sunshine Aluminum Composite Panel © 2024 Condé Nast. All rights reserved. WIRED may earn a portion of sales from products that are purchased through our site as part of our Affiliate Partnerships with retailers. The material on this site may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, cached or otherwise used, except with the prior written permission of Condé Nast. Ad Choices