Over the years, I’ve been curious to dig deeper into the world of the manufacturing in China. But what I’ve found is that Western anecdotes often felt surface-level, distanced, literally and figuratively from the people living there. Like many hackers in the west, the allure of low-volume custom PCBs and mechanical prototypes has me enchanted. But the appeal of these places for their low costs and quick turnarounds makes me wonder: how is this possible? So I’m left wondering: who are the people and the forces at play that, combined, make the gears turn?

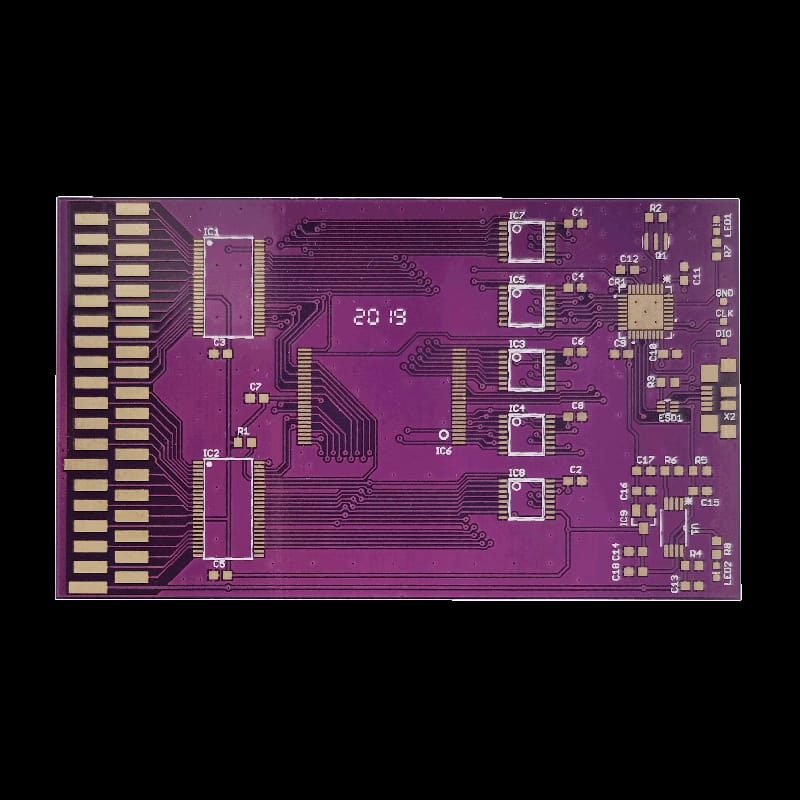

Enter Prototype Nation: China and the Contested Promise of Innovation, by Silvia Lindtner. Published in 2020, this book is the hallmark of ten years of research, five of which the author spent in Shenzhen recording field notes, conducting interviews, and participating in the startup and prototyping scene that the city offers. Flex Pcb Capabilities

This book digs deep into the forces at play, unraveling threads between politics, culture, and ripe circumstances to position China as a rising figure in global manufacturing. This book is a must-read for the manufacturing history we just lived through in the last decade and the intermingling relationship of the maker movement between the west and east.

Lindtner does a spectacular job detailing why Chinese manufacturers will readily duplicate and resell existing designs. The answer is multi-faceted but involves, in part, a culturally distinct approach to designs. Duplication offers a means of reverse engineering, a way of understanding how something works. In fact, a number of designs known as gongban (pg 94) regularly circulate openly across factories as templates. The consequence is not only the means of manufacturing something akin to the original, but a way of producing original designs too via customizations that can freely run wild. Lindtner’s punchline in all of this is that the copy is essentially the prototype.

Of course, bootstrapping manufacturing pipelines for existing products does have the consequence of building a Western perception of Chinese manufacturing as a sort of copycat. Lindtner engages with this idea as well, noting how some Western maker labels devote extra work to qualify their means of production in China as genuine (think Arduino “Genuino”) while others emerging directly from China like Seeed Studio have had to push through this perception to break into Western markets.

With gongban, manufacturing in China has developed under circumstances where unlicensed sharing is the norm. In a way, this culturally distinct approach challenges the Western style of binding designs to terms set by the creator. It’s almost as if the west were to operate with permissive open source licenses being the default, and it begs the question: what kinds of innovation we would see if this kind of relationship to designs existed in the west?

None of this manufacturing growth has happened in a vacuum. It turns out that a collection of forces loosely motivate this sort of rapid manufacturing development in China.

First, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has somewhat adopted the promise of the maker movement and used it, in part, to spur economic growth by creating a strong connection between making and entrepreneurship. Here, starting off as maker puts you on a path towards happiness by ultimately starting your own business. It’s no coincidence that the west now regularly sees Shenzhen as the “Silicon Valley of Hardware.” Both careful branding and financial investments via recognizing Shenzhen as a “Special Economic Zone” have made this the case.

On the other hand, the capacity to manufacture electronics cheaply has also brought in business from the west. Lindtner notes a number of Western articles comparing manufacturing in China as “going back in time,” and she ties this frontier-like perception to other scholarship that digs into the aftermath of Western colonialism. Overall, the politics between west and east are vastly complicated, and this section of the book makes for an eye-opening read.

This article is only teasing you with a few highlights. Fret not, Dear Reader, with just over 220 pages and a thick bibliography to sink your teeth into, there’s plenty left to walk through. If you’ve ever been curious to step into the world of manufacturing in China, this book is a must-read. Give yourself a few afternoons, and let the details of prototyping in China draw you in.

I’d say after 2020s semiconductor shortage this book aged like a fine milk.

How so? We saw a bunch of Chinese SoCs gain prominence amid the shortage of Atmel and ST parts. If anything the culture of open copying gave many manufacturers crosses to keep shipping products with minimal changes to hardware and firmware.

Isn’t that kinda what patents were supposed to be for? Sharing innovation openly but also protecting the right of the original person to profit from the work? Sounds like China maybe embraces development over hugely expensive patent litigation. And original developer still gets a production run and profits.

Sorta. Patents are to stop information being lost because of trade secrets, release the info and we’ll let you sue the copycats for 20 years.

Patents tend to slow innovation though, look at 3D printers or digital calipers. Or what happened with Wago connectors. Once the patent ran out all sorts of new designs hit the market, even ones that people had been asking the patent holder to make for years. Now Wago are reduced to copying the Chinese “knockoffs” rather than being an innovator.

The Chinese philosophy is more community minded, copying is perfectly ok so long as you make you version better than the original. The original designer gets nothing out of this, but they’re welcome to take your improvements and mix them back into their design, and around it goes.

If all of this sounds more open source than patent, well there’s a reason open source advocates are often called godless commies. I don’t have a problem with patents, but the current system ($$$ wins) needs a bit of a rethink.

“The Chinese philosophy is more community minded, copying is perfectly ok so long as you make you version better than the original.”

Except in the real world it usually ends in a race to the bottom until the products turns into a hazardous piece of […].

With genuine Wago connectors I can be (more or less) sure that they’ll work flawlessly for decades. How do I know that some generic “Woge” connector sold in a local supermarket wasn’t made from recycled beer cans just to save $0,03? Can I trust it not to become a resistor and fire hazard in my $180,000 home?

Same reason why sparkies use Flukes instead of DT830s.

A “race to the bottom that produces hazardous pieces of crap” is not the exclusive purview of Chinese philosophy. See: the hypercapitalistic behaviour of Walmart. Well known for enticing small businesses by offering to stock their products, then over a few years demanding the same product to be produced for less and less, and if the producer ever baulks or falters then creating an own-branded copy in very short order.

I imagine as consumers we could counter that by demanding products cost more and no more sales. Throw in “made in America” to sweeten the pot.

“better” includes “make it for less money”.

To really understand China, you have to have lived and worked there. The author has obviously done that. I myself have also lived and worked in China for 10 years.

“It’s almost as if the west were to operate with permissive open source licenses being the default…” typo? Other than that, great article!

Two aspects I still worry about when ordering pcbs etc are the environmental impacts there and issues around worker safety and rights… How much of the low (financial) cost is paid for by high costs that we don’t see? (Is waste managed well? Which products are made by forced labour in Xinjiang? Etc). I know that there are interesting, innovative things happening, but I really hope the book covers these issues too: in the West a lot of the protections we now take for granted were, for example, achieved through trade union action (paid holiday, safer working environments, equal pay for equal work) – TUs I don’t think are tolerated there.

I develop prototypes and custom software, and I wanted to support local businesses.

However, when just calling a local PCB manufacturer will set you back $160, and that’s excluding the actual work (another $160 per hour + materials and shipping), the business case is pretty clear to me:

Tax plus Customs Fee is $160 and then $2-$90 for 5-10 PCBs plus shipping. Shipping time might be longer, but that leaves time to make other hardware, source components and write software.

So, it’s a compromise between price and “moral” in a lot of cases. And to me, price wins.

OSH Park is US-based and they’re great. Somewhat more expensive than the Chinese shops, but you’ll get your boards in about the same time.

Anything from the U.S. will be an additional $30 + the $160 Tax and Customs Fee..

(I’m based in Denmark ;-) )

Wow, you are being robbed over there. In Poland the fee is about 20$ when shipping with DHL, or zero if you are patient enough to send the PCBs through regular mail (it took about two weeks last time).

Andrzej, yup… Largest criminal organization in Denmark is the government and especially, the “IRS”…

Thanks for bringing this book to my attention. It’s my birthday – so I ordered a copy :-)

Thanks for covering this. Silvia is great!

Call me an unprincipled cheapskate, but I am hoping that Hand386 gets gongban-ed

Good article despite a few obvious typos ;) The big problem in this gongban is the sharing of designs is often done without the original creator’s consent. With open source, we actually get to decide under what terms our software can be used/distributed/copied, and we have some sort of legal recourse or public shaming against those who don’t comply. However with gongban it’s a free-for-all and THAT in my opinion is not fair. It’s very different from open source. As a maker of products which I want to sell to businesses, I want to avoid China for that very reason, but to save costs I have no choice (because making locally can easily cost 10x more money). It’s a bit of a conundrum, but I think the best solution for the moment is to only give them useless pieces of your product design (ex: just the PCBs, no parts assembly or BOM), and handle all the rest locally (reflow, soldering, hardware assembly, packaging). I think the cost of hiring a couple energetic teenagers for USD $10/hr to assemble electronics and pack boxes locally would be morally better than the slave-workers in China, and it’s not that much more expensive.

Explain to me how child labor at poverty wages in the US from “slavery work” in China

At least in theory. In practice, OS projects often have no practical legal recourse to abuse (with the exception when the OS project is produced primarily by a corporate entity with capacity and willingness to litigate) with “naming and shaming” being equally ineffective regardless of location. For example, Nintendo’s well known commercial abuse of open-source emulation software.

The standard of living of the average urban continental chinese worker isn’t that much different from that of an USian’s, and it’s far higher than that of workers employed by USian corporations in their colonies like Mexico.

Continental China simply has economies of scale on their side.

Please be kind and respectful to help make the comments section excellent. (Comment Policy)

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Pcb Types By using our website and services, you expressly agree to the placement of our performance, functionality and advertising cookies. Learn more